Super-charging React with ImmutableJS

At Hootsuite, we’ve been working on restructuring our front-end architecture using React and Flux. This has given us the opportunity to explore the benefits we gains by structuring the data on the front-end as immutable collections. As part of the Engagement team, a group of us are working on Streams, the part of the product our users directly interact with when they use the Hootsuite dashboard. This is one of the major chunks of the product being migrated over from Backbone and jQuery.

For those who are new to React, it is a JavaScript library for building user interfaces, built by the folks over at Facebook and Instagram to enable them to build large web based application with data that changes over time. It is often valuable to think of React as the view part of the Model-View-Controller pattern.

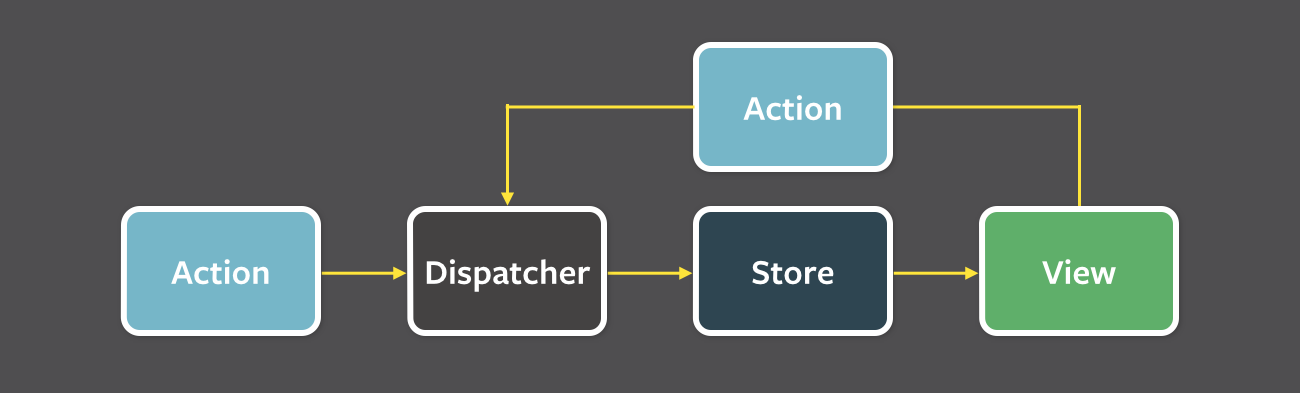

Flux is an architectural pattern that complements React by utilizing a uni-directional data flow. When a user interacts with a React view, the View fires an Action that goes through a Dispatcher to update a Store that holds the application’s data and state, which in turn updates the Views. Uni-directional data flow ensures that a change in application’s state is updated wherever the state is used without forcing the developer to update the code everywhere the state is used.

You can learn more about React and Flux by reading this in-depth post written by my teammate, Catherine.

Making React Even Faster

As part of building out our new front-end, it was important that performance was a concern that we kept in mind. With customers relying on our product to be highly efficient and robust, this was going to be a primary concern as we moved over to React and Flux. A key improvement metric that can be looked into with regards to React is how often a component re-renders. That’s where immutable data comes into play and provides a better way to optimize the process of re-rendering.

The way React works is by maintaining its own fast implementation of the DOM tree called the virtual DOM. Whenever there is a change in the UI, React makes a new virtual DOM and compares it with the old one, and if they’re different, it updates the actual DOM, minimizing the number of mutations. To improve performance, we need to ensure that only the part affected by the changes in the data is re-rendered. To allow developers to do this, React provides a component lifecycle function called shouldComponentUpdate which runs every time a component is re-rendered. We can couple this function with immutable data structures to ensure that a re-render only happens when the data has actually changed.

The Problem with Mutable collections

Let’s look at some of the problems that we may run into if incase we were dealing with mutable data and states within React. Imagine a Message component that takes the data necessary to render a message on the page. If a user was to edit the message text, we want to ensure that the component reflects the change, so we might have something like this in our lifecycle function that allows us to re-render only if the message text has changed when we receive a new list of messages.

// Message Component

shouldComponentUpdate: function(newProps, newState) {

return this.props.text !== newProps.text;

}

However, with large and complex data structures this becomes an issue because we’re passing around pieces of the the application’s state as Objects and an identity (triple equal) comparison fails for Object in Javascript, even if the values are the same across both:

var obj1 = { foo: 'bar' };

var obj2 = { foo: 'bar' };

obj1 === obj2; // false because obj1 & obj2 are different objects, even if values are the same

Instead, we need to do a deep comparison to determine whether the values we’ve received have actually changed. However, with nested objects, we would need to do a recursive deep comparison operation that is really expensive. And since such a comparison would need to be done every time shouldComponentUpdate runs, which React invokes very frequently, we would take a large performance hit.

Yet another problem we run into with JavaScript objects are references to the same object returning true when compared even if the values are changed like so:

// Same reference

var x = { foo: 'bar' };

var y = x;

y.foo = 'qux';

x.foo; // 'qux', because x has also changed

x === y; // true even though 'apparently', value was changed

ImmutableJS to the Rescue

We can solve these problems with immutable data. ImmutableJS is a JavaScript library that provides immutable collections which provide two important guarantees. The first being that once an immutable collection is created, it cannot be changed. And the second being that a new collection can be created from an existing one by mutating the original one. Moreover, any changes to a collection results in a new one being made. This avoids any false truthy values arising from comparisons of objects that may have the same reference.

var Immutable = require('immutable');

var x = Immutable.Map({ foo: 'bar' });

var y = x.set('foo', 'newbar');

x === y; // false, as required since value at foo has changed

var z = x.set('foo', 'bar');

x === z; // true, as required since value at foo has not changed

What does that mean if you’re using Flux stores to manage the data as a state of the UI? Well, it means that the data within the Flux stores will need to be modelled to be immutable. With the state of our UI being immutable data, we gain the ability to perform very fast comparisons. This allows us to use such comparisons within the shouldComponentUpdate without negatively affecting the performance.

Shared Structure

One way that immutable collections achieve space and time efficiency is through sharing structure. Whenever a new collection is made from a new one, it reuses the parts that haven’t changed, and only creates the parts that are new, or have changed. This avoids the time lost spent copying an entire structure, making it time efficient. Moreover, the memory footprint is also smaller since the same parts are being used for this new structure. We can illustrate this through the following example of a tree structure where a we’re updating a node.

When we need to make changes to the blue node, we create a copy of it, marked by the orange one. It can still point to its old child since we don’t need to change that. However, the parent of the blue node needs to point to the new one, so we need to create a copy of it, marked by the red node, and point to the copy of the blue node, however, we can still reuse the parent’s left child. Notice how more than 50% of the structure is being shared.

Arrays and Objects as Immutable collections

Now that’s pretty cool but what about Arrays and Objects? Arrays, which are a list of values, and Objects, which are key value pairs are the bread and butter of our modern applications. Immutable provides two highly efficient implementations of these two data structures. Arrays are represented by Bitmapped Vector Tries, whereas Objects are represented by Hash Array Mapped Tries. Let’s take a look at what these two are and how they work.

Bitmapped Array Tries can be imagined as a tree of arrays. All the actual values are only stored in the leaves. In the example below, let’s say we wish to find the value ‘114′. First, we’ll convert the number to a binary. This gives us 01110010. We lookup the first two most significant bits. We get 01, which is the number 1, so we follow along index 1 of our first array. Next we lookup the next two significant bits and we get 11. That’s the number 3, so we we follow along the index 3 of our next array. Then we lookup 00, which corresponds to index 0. And lastly, we lookup 10, which corresponds to index 2. And voila! We’ve found our value ‘114′. If in case we wanted to store something at value ‘114′, say a string ‘foo’, we’d lookup value using the algorithm described and place the value in the 114th place. This implementation is used by the immutable collection called List and can be used as an Array.

Hash Mapped Array Tries work in a similar fashion, the keys and their corresponding values are only stored at the leaf nodes of the tree. If we wish to find a value associated to the key ‘m’, we first pass the key through a hash function. A hash function can be thought of a function that takes anything and returns a number. Let’s say that for ‘m’, our hash function gives us the value 45. We convert 45 to binary, and this time, instead of looking up the most significant bits, we lookup the two least significant bits first. Which, in this case, are 01. We go follow through to index 1, we lookup the next two least significant bits, which are 11, so we follow through to index 4. Then we lookup 10, which corresponds to index 10. And ta-da! We’ve found the key ‘m’. We lookup the value and return ‘munchkin’. A hash array mapped trie has the ability to increase its dynamically, unlike a conventional hash map. This makes dealing with collisions (adding two values to the same node) significantly less expensive. This implementation is used by the immutable collection called Map and can be used as an Array.

In Conclusion

How is all of this useful to us as JavaScript developers? It turns out that JavaScript engines are highly optimized for dealing with bit-shift operations that the data structures used in building immutable collections rely on. This provides us with extremely fast implementations of Arrays and Objects, which are Lists and Maps respectively. Coupled with React’s ability to reconcile the DOM tree high effectively, this allows us to do very fast comparison when the state of our application changes, and update the UI in a manner where anything that hasn’t changed, does not effectively re-render. By doing so, we are able to optimize the rendering process to a point where we’re only re-rendering only the things that have truly changed in the application state, which is represented by the data received by our application. And with that, we are able to take React, one of the fastest libraries we have for building user interfaces, and make it even faster.

My heartiest thanks to Alexandrine and Noel for their feedback on this write up.

References & Additional Reading

- David Nolen – Immutability, interactivity & Javascript (FutureJS 2014)

- Lee Byron – Immutable Data and React (React.js Conf 2015)

- Jean Niklas L’Orange – Understanding Clojure’s Persistent Vectors (Part 1)

- Phil Bagwell – Ideal Hash Trees

The resources above were essential towards helping me understand immutable collections and their implementation details described in the GIF illustrations above. The illustrations of the tree structures were drawn in Sketch and then converted to a GIF using Photoshop.